We're an all volunteer website and need your help to keep going. Here are five ways you can contribute: 1 Donate 2 Buy something 3 Submit a story 4 Volunteer 5 Advertise

New in the gift shop, virtualitalia.com logo wear and use items!

|

PLEASE NOTE: We are experiencing unexpected

technical difficulties caused by our web host. We apologize for

the inconvenience. During your visit you may experience service

and page interruptions - we are in the process of fixing everything and hope to be

fully back on our feet soon.

chicago's italians

The overall result of all the positive and negative forces during the post World War II era was that, except for a few noteworthy pockets of Italian settlement, Chicago's old Little Italies were destroyed. With them have gone the sentimental sense of identity and security that the continuity in customs and familiar faces of the old neighborhood offered. Whatever political power that the Italians could muster from geographic concentration was also undermined. Henceforth, there would be no geographic base for the community. This was replaced by a smaller community of interest based almost entirely upon voluntary association and self-conscious identification with Italianess.

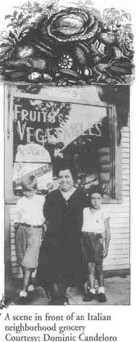

The campaign to support the Villa also resulted in the establishment in 1960 of Fra Noi (Among Us). A monthly English language paper, Fra Noi functioned as a house organ for the Villa. Featuring local articles on politics, people, organizations, major contributors to the Villa, sports, recipes, and cultural and religious topics, Fra Noi has in its four hundred issues reinforced a sense of Italianess and community among its 12,000 subscribers and their families. In 1985 Fra Noi passed from Pierini into the hands of the third-generation professional journalists who have broadened the paper's circulation, advertising revenue, intellectual scope, and even the size of its Italian language section. Given the current geographic dispersal of the 300,000 Italians in the Chicago area, it is hard to conceive of any meaningful way in which the term "community" could be used to describe that population if Fra Noi and the Villa did not exist. A brief demographic analysis of the Italians in the city in recent times yields varied conclusions. Census figures for 1970-1990 show Italians in the city to have above-average incomes and to be slightly under-represented in the professions. Other studies have shown that the Italians along with the Poles, African-Americans, and Hispanics are woefully under represented on the boards of directors of large corporations. Figures for educational attainment show Italians to be below average, but this can be explained in part because the oldest cohort of Italians had little or no formal education. In 1980 statistics show the highest concentration of people of Italian ancestry in the Dunning, Montclare, and the Belmont-Cragin areas of the northwest edge of the city limits where approximately 20,000 of the 138,000 city Italians live. This forty-block area is shared with second and third generation Poles but contains hardly any African-Americans. The ambiance of the neighborhood also reveals the ethnicity of the zone. It features a large grocery specializing in Italian imports and a genuine Italian-style bar (Bar San Francesco) complete with espresso, gelato, and card-playing Calabresi in the backroom. Many of the stores and businesses on Harlem Avenue are owned and operated by Italians, many of them recent (1970s) immigrants. Both the statistical and the impressionistic evidence point unmistakably to the fact that the era of the poor Italian-American is long gone. They are financially comfortable as a result of success in family business, the acquisition of a skilled trade, or through unionized factory work. Moreover, the under-consumption of previous generations, the slow accumulation of real property, and family economic cooperation reinforce their economic status. They have achieved the American Dream except for one thing � respect.

...to be continued! Related Items: |

© 1998-2005 by virtualitalia.com unless otherwise noted

World War II changed everything for Italian Americans. It Americanized the second generation. The G.I. Bill opened up the first possibilities for a college education and the first opportunities to buy a new suburban house. Other government policies such as urban renewal, public housing, and the building of the interstate highway system combined to destroy their inner-city neighborhoods. First was the building of the Cabrini-Green Housing Project, which helped drive the Sicilians out of the Near North Side in the 1940s and 1950s. Then came the construction of the expressway system on the near south, west, and northwest sides, which dislodged additional Italian families and institutions, including the church and new school of the Holy Guardian Angel. The exodus headed west along Grand Avenue, eventually reaching Harlem Avenue. In the early 1960s Mayor Daley decided to build the new Chicago branch of the University of Illinois in the Taylor Street neighborhood. This meant that approximately one square mile of the heavily Italian neighborhood would have to be demolished. Almost simultaneously the Roseland-Pullman Italian Community fell victim to real-estate block busters who profited from the expansion of the black ghetto by scaring white residents into abandoning their neighborhood and their new Church of St. Anthony of Padua.

World War II changed everything for Italian Americans. It Americanized the second generation. The G.I. Bill opened up the first possibilities for a college education and the first opportunities to buy a new suburban house. Other government policies such as urban renewal, public housing, and the building of the interstate highway system combined to destroy their inner-city neighborhoods. First was the building of the Cabrini-Green Housing Project, which helped drive the Sicilians out of the Near North Side in the 1940s and 1950s. Then came the construction of the expressway system on the near south, west, and northwest sides, which dislodged additional Italian families and institutions, including the church and new school of the Holy Guardian Angel. The exodus headed west along Grand Avenue, eventually reaching Harlem Avenue. In the early 1960s Mayor Daley decided to build the new Chicago branch of the University of Illinois in the Taylor Street neighborhood. This meant that approximately one square mile of the heavily Italian neighborhood would have to be demolished. Almost simultaneously the Roseland-Pullman Italian Community fell victim to real-estate block busters who profited from the expansion of the black ghetto by scaring white residents into abandoning their neighborhood and their new Church of St. Anthony of Padua.

Attaining their final goal is the stated or unstated purpose of the hundreds of voluntary associations that Chicago Italians have formed. Prominent among these is the Joint Civic Committee of Italian-Americans (JCCIA). It was established in the 1950s in response to an effort by the Democratic party to drop a respected Italian-American judge from the electoral ticket. An important part of the Capone legacy is the assumption in the public mind (and among Italian-Americans themselves) that every successful Italian-American is somehow "connected."

The JCCIA since its founding has maintained a downtown office with a director, a secretary, and volunteers and is generally conceded to be the spokesman for the Chicago Italian-American community. Its Anti-Defamation Committee has used an effective combination of quiet influence, outraged protest, and award-giving flattery to nudge the news media toward more objective treatment of Italians. One major achievement has been the cessation of the use of Italian words such as Mafia and Cosa Nostra in favor of the more neutral "organized crime."

Oriented toward the regular Democratic organization, the officially "nonpartisan" JCCIA's major patron was Congressman Frank Annunzio, who fashioned for himself on the national scene the role of "The Leading Italian American Congressman." The most important annual function of the JCCIA is the Columbus Day Parade, which attracts almost every politician in the state regardless of race, ethnicity, or party. The Columbus Day event shows off the Italian community's power and influence.

In the early 1960s the JCCIA forged an alliance with the Villa and Fra Noi, which gave increased credibility to all concerned. Together the agencies have sponsored a dizzying array of cultural, folkloric, and social events that range from Italian language classes to debutante balls.

Attaining their final goal is the stated or unstated purpose of the hundreds of voluntary associations that Chicago Italians have formed. Prominent among these is the Joint Civic Committee of Italian-Americans (JCCIA). It was established in the 1950s in response to an effort by the Democratic party to drop a respected Italian-American judge from the electoral ticket. An important part of the Capone legacy is the assumption in the public mind (and among Italian-Americans themselves) that every successful Italian-American is somehow "connected."

The JCCIA since its founding has maintained a downtown office with a director, a secretary, and volunteers and is generally conceded to be the spokesman for the Chicago Italian-American community. Its Anti-Defamation Committee has used an effective combination of quiet influence, outraged protest, and award-giving flattery to nudge the news media toward more objective treatment of Italians. One major achievement has been the cessation of the use of Italian words such as Mafia and Cosa Nostra in favor of the more neutral "organized crime."

Oriented toward the regular Democratic organization, the officially "nonpartisan" JCCIA's major patron was Congressman Frank Annunzio, who fashioned for himself on the national scene the role of "The Leading Italian American Congressman." The most important annual function of the JCCIA is the Columbus Day Parade, which attracts almost every politician in the state regardless of race, ethnicity, or party. The Columbus Day event shows off the Italian community's power and influence.

In the early 1960s the JCCIA forged an alliance with the Villa and Fra Noi, which gave increased credibility to all concerned. Together the agencies have sponsored a dizzying array of cultural, folkloric, and social events that range from Italian language classes to debutante balls.